This coffee company inspired me today | 005

Keba Konte talks about Red Bay Coffee’s commitment to delivering quality coffee while being a vehicle for intersectional change within the Bay Area

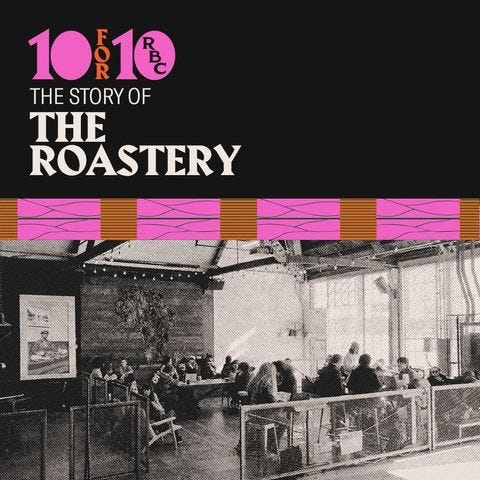

The above photo shows Red Bay Coffee’s headquarters in the Fruitvale District of Oakland (the post is from their Instagram page — there will be quite a few embedded posts, so feel free to click on them to learn more).

Towards the top of the right side of the building, their motto is displayed:

"Beautiful coffee to the people."

A seemingly simple motto, right?

… until you learn more about the story behind it.

I've been following Red Bay Coffee's story for several years since I started hitting up their roastery in East Oakland.

After a handful of visits to RBC, I realized they aren’t your typical coffee company. I felt a purposeful and intentional energy from the front-of-house and back-of-house team members. Once I followed their Instagram account, I became even more curious about RBC and its founder, Keba Konte's story.

Today, we'll talk to Keba about his journey to creating RBC with a community ethos you can taste in the coffee.

Table of Contents

Why is community important to Keba

How RBC has been building with a community mindset

The challenges RBC has faced

Advice Keba has for businesses leading with a community mindset

What RBC needs from the community

Derrick: As early as you can remember, why has community been important to you?

Keba: I was born in 1966 and grew up in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in San Francisco to a mixed-race couple. It was my older sister and me; when my mom was 22 or 24, my parents adopted our younger sister, Celeste. When you think about Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s, it was a combination of the "Free Love" hippie movement, the Free Speech Movement, and the Black Panther & Black Power Movements. So all these movements, the creativity and free-wielding spirit of San Francisco, and the adoption were all happening around me.

Adopting when you have two children is a very community-centered piece. You are reaching out to care for someone else's children they could not care for; that is the epitome of community. My middle school was literally named the San Francisco Community School. It was also an alternative school, and in terms of teaching style, we were always on field trips and camping trips. Skip forward to college, where I was a San Francisco State University student. I was on the wrestling team for four years, from 18 to 22 years old — as an athlete, you're also a full-time student. Then, I became a father when I was 19 years old, so for my last two years of college, I was a dad, had a part-time job, and was a full-time student — it was a lot. I had a lot of dreams about going away to the East Coast and trying to get a wrestling scholarship at some of these East Coast schools, like an HBCU or something. But when I became a dad, I was like, "All right, I'm going to be here." It wasn't even a second thought. I had to be here to parent my daughter, Jessica. So, from there, I settled into the Bay Area; this will be where I continue to call my home.

Wrestling was a huge commitment that required two to three hours a day, five days per week. I had to commit to road trips, competitions, and even my summers. Once my wrestling career was over, I had a little void.

All of this happened in the late 80s, and during this time, the SF State campus was a hotbed of political activism. Our professors were the students in the student movements that created the first Ethnic Studies program in the United States. All those radical students returned and became professors: Angela Davis, Oba Tashaka, Laura Head, and others. We're being taught by these very conscious and radical thinkers and reading revolutionary texts and biographies.

I was combining this education with what was happening in the world then: the Rodney King beating, the O.J. Simpson decision, the Gulf War. These activities were galvanizing and formative, and they happened as I became a man and formed my thoughts outside of school, sports, and my home. I became radicalized through this. I joined an outside organization and was part of the founding group. And it was an anti-war organization called the Roots Against War, RAW for short. We organized rallies that drew thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, into the streets. We were super international: Palestinians, South Africans, Cubans, and Irish. We had people like Jivika, who was from Sri Lanka. We had people who weren't students, just activists and people who cared. I was moved by these activists dedicating so much time to organizing, making flyers, making banners and signs. Nobody was getting paid either. They weren't motivated by money; this was inspiring and moving. I was learning about struggles in South Africa, Sri Lanka, and Mexico; I was learning about the student movements in these countries — the concept of "they thought they buried us, but they didn't know we were seeds." There was the whole movement and the bonds we created. My belief is that your best friends are friends you make under conditions when you're struggling. Whether in school, work, or activism, these are bonds I still hold dearly.

Then I joined another group, the All-African People's Revolutionary Party, abbreviated as the A-APRP — we organized African Liberation Day. The mantra was about educating and organizing your community. Kwame Nkrumah was the founder, and then Kwame Ture (formerly known as Stokely Carmichael) led the party. This group wasn't about direct action in the streets, like the other groups I was involved with. They were more about learning, educating, and reading books. There were books on Africa, African history, and socialism and how that fits into African life — these years formed my political ideology as a Pan-Africanist, from a global perspective to a local one — just being a hands-on activist, supporting community people in all sorts of ways.

Derrick: I had a feeling you would have a cool story around that question, and you didn’t disappoint! Thank you so much for sharing so much of that. There's a lot to unpack there, and we will likely unpack more as the conversation continues, but that was incredible.

How have you built Red Bay with community at the forefront of what you're doing here? What are specific ways that you have done that? I know you're B Corp, and I know that you're hiring people of color and making that a priority, but like outside of some of these things that you've shared on social media, are there other specific things that you want to call out that have been a pillar of how you built this?

Keba:

The product is just as important as the mission

When it comes to mission and community-driven companies and organizations, there's no shortage of them. But one thing I've noticed for mission-driven commercial products is that the mission is often very forward, and they're nailing it, but they don't always nail the product. And you can find someone to support you and check you out once. If it's a $7 chocolate bar or a $15-20 bag of coffee and you're having that cup of coffee in the morning, it's part of your ritual, and it's not on point, you're just not going back. And I don't blame them. So, no matter what else we did, I always knew we had to get the product right, along with the mission. We had to walk and chew gum. We had to be about community-driven business, quality control, quality assurance, taste, and developing and hiring the best people.

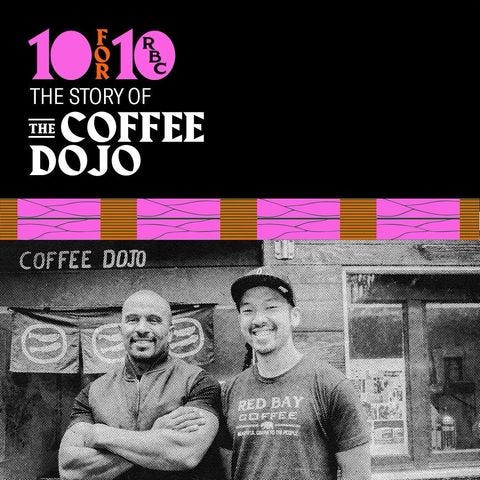

Red Bay's first employee

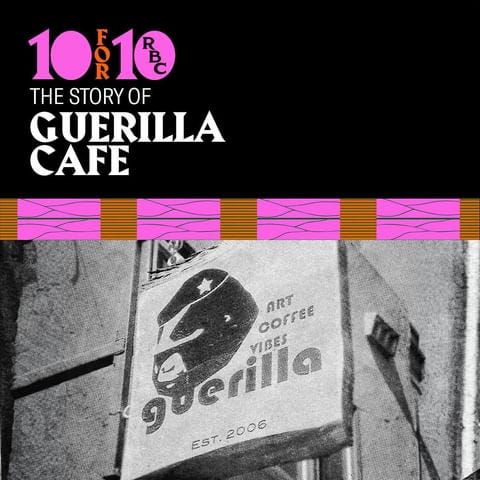

For instance, our first employee, Kori Chen, reached out to me because he was writing something and wanted to interview me when I had Guerrilla Cafe.

He interviewed me for a little blog called Chasing Cheddar. Man, I just really admired this cat. He had a lot of good energy and was out organizing in the streets of New Orleans and the South; he was bold and community-driven. His parents were legendary activists in Oakland, Chinatown, and the Bay Area. He was involved with prison reform. He knew many people in circles around that, and he brought us to some of those meetings and brought these issues around formerly incarcerated and second-chance citizens to Red Bay Coffee; this was one of our early hiring initiatives. We knew what they needed and that recidivism was (and still is) a big issue because whenever you had to fill out a job application, there was a box for "Have you ever been convicted of a crime?" So we've participated in trying to get that box eliminated from job applications. We hired some of our first few people from some of those communities.

Ultimately, I'm still new to business and entrepreneurship. I did start Guerrilla Cafe, but my past entrepreneurial efforts were maybe more on the "hustle" side than the official side of entrepreneurship. I'm still learning to this day. A lesson has been our shipping container concept. The idea was that the employees would keep the profits, and Red Bay Coffee would place this container and set it up for business. We would sell coffee to that outlet in the wholesale, and we would be making money on wholesale, and the team that managed it would have their salary and keep the profits. In retrospect, I was a little naive, and what I had not anticipated was how hard it would be to make a profit and what would happen. Eventually, we struggled to make a profit there at that location. But we still wanted to give the employees some raises, but by giving them raises, it made the profit even further out.

Equity in the company

They collectively decided to forgo that model and pushed to get shares in the company (as a whole and not just that one single outlet). We wanted to make sure to offer stock options for every employee, not just the executive suite, not just the managers, but every single barista has stock options.

Kickstarter

For funding, we did a Kickstarter, and at that time (2015), the most anyone had ever raised in the coffee category was $50k. However, we needed more than that, so we set the goal at $80k. The thing about Kickstarter is that if you don't hit your goal, you don't get the money. Even though we had just started a year before, I felt confident (I don't know where my confidence was coming from) that the community was behind us and that we could raise that money. We had over 800 people contribute, raising $88k. We blew past through the record. The campaign was strong community engagement.

Other activities include donating coffee. Sometimes, for example, after getting rained out at the farmer's market, we take our van out to some of the homeless encampments under the freeway bridges and give coffee for free to the homeless people.

When we picked our headquarters, we had community in mind. We're in the heart of the Fruitvale District, on the corner of Fruitvale Avenue and International Boulevard. It's not that there's no coffee around here, but there's certainly no specialty coffee. There's Hasta Muerte up Fruitvale, which we love, but a coffee shop to this scale, you just won't find it.

We placed it out here in East Oakland, where you're just not used to walking up to an oasis like this, especially for coffee, where there is top-of-the-line equipment, a beautiful space, two-story ceilings, big windows, lounge seats, plants everywhere, beautiful modern designer lamps, and an environment that's worthy of the community, and serving products that make sense. We can't forget it's still a commercial rental, though, and our prices aren't discounted because we're trying to pay a fair wage and buy quality products. But the fact that we're here on this corner, open daily, is a testament to our love for this community.

Derrick: In the documentary that y'all did with Upwork called “Beautiful Coffee,” there was a segment where you talked about replacing the words "supply chain" (based on its meaning within the context of slavery) with "value stream."

Can you highlight and celebrate specific partners throughout your value stream within this conversation to show that this is an ecosystem?

Keba: We're intentional about the partners and people we connect with. For some of these partners, you'll taste their element of our product. Then, some are in the background, and you'll never know. The people who dug the trenches, the people who did the construction, the plumbers, the electricians, the architects — we're very intentional around finding and choosing underrepresented professionals, laborers, all the above who are at the top of their game.

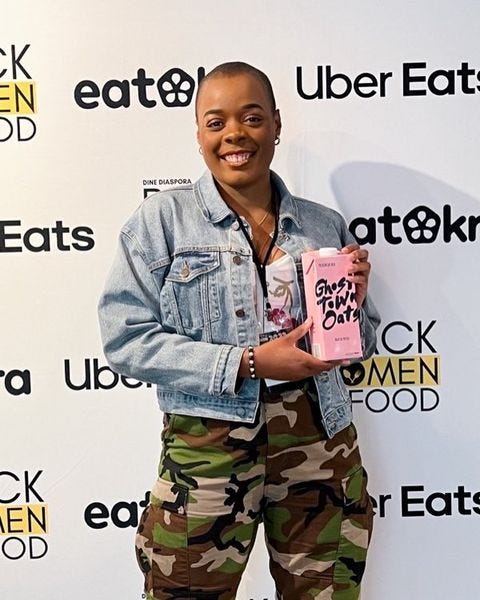

Ghost Town Oats

One great example from the value stream is that we just launched a product called Ghost Town Oats. Ghost Town Oats is a new product from a Black and Queer-founded oat milk company founded by Michelle Johnson (pictured below). They're the first Black-owned oat milk company in the country. I glow with pride when she says she's a former Red Bay employee. It was a brief pre-pandemic employment. We brought her on as our trainer and educator, and then the pandemic hit and threw everybody for a loop.

Red Bay mocha

Our mocha product starts with two different coffees with espresso. One is from Tanzania. One element comes from Burundi and a Burundian woman who left tech to go back home and start this. She's also the importer of her coffee at her farm, which she's a producer of.

The other element is Guatemalan coffee imported by a Guatemalan-led organization called Onyx. Not to be confused with the coffee brand Onyx, Onyx is an importer or coffee importer of green coffee. And that's Guatemalan coffee grown by Guatemalans, obviously imported from a Guatemalan group.

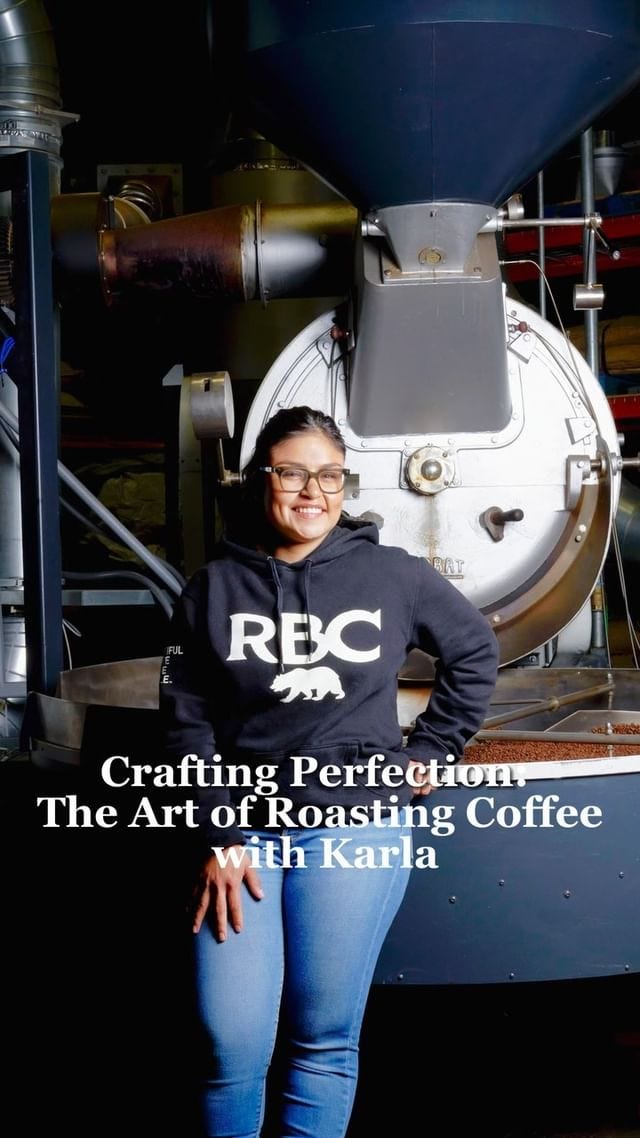

We’ve had two coffee buyers: the first was Alicia, a Black woman. Now, we have Karla Mancio, a Guatemalan woman. She's the buyer and developed the roast profile.

Our two production roasters, Solomon (he’s in the video below) and Ashley (she’s in the photo below), a Black man and a Black woman, are brilliant at what they do and super dedicated.

The coffee roasted at our cafes is made mostly by Black and Brown baristas. So we've got this shot of espresso, Ghost Town Oats, and cru chocolate mocha from Karla.

There are also other examples of the bakers and suppliers that we use. Then, when you buy a Red Bay Coffee drink, right on the cups, the beautiful African print cups are designed by our Chief of Brand, Rachel, a Black woman, and her Head of Design, a Black man named Nick James. So you got that cup, which is compostable, and you've got the chocolate, the milk, the espresso — that's how we think about the value stream.

Supply chain and some people use the language they were taught, but often there's so much in it. And when you do, it's not about being politically correct. It's really about how our language informs how we think about the world and our choices. And when you think of just even the metaphor, just myself as an artist and thinking about words and metaphors and pictures that come to my mind. Like why do we, as a Black-owned company celebrating this liberation, need to keep thinking about chains as a metaphor, like who needs it?

A stream is water and life-giving. It moves where it needs to move. It could separate or join. We go out of our way to be intentional about who we're doing business with and who we buy from.

Derrick: What values do you consider when bringing on a potential partner within the value stream?

Keba: One low-hanging fruit is the demographic: Are they from an underrepresented community? Are they women, people of color, disabled, or immigrants?

The next layer under that is, for example, on the farm level, are they positively impacting the environment/their environment? What are their practices? Are they not exploiting children? That seems easy, but that's not always the case with coffee, chocolate, or things from developing countries. Do they have an interesting story? Are they doing other things in their community? For example, Alba Rosa Claros is doing amazing work supporting trafficked women and is one of our green coffee suppliers. Sometimes that's enough. If you're just a Black woman here, you're baking and trying to survive, and they don't have to be B Corp certified or anything like that. It's a struggle just to exist and be in business. So that's very often enough for us.

Derrick: What are the struggles of a business like yours that wants to be community-minded and intends to continue to operate in this way? What struggles might people not be aware of or see looking in from the outside?

Keba:

Running a business isn’t easy

It is really challenging to run a business and break even. It may be easy for some people, but it's challenging for everybody I know and from my personal experience. The things that can go wrong are employees, funding, customer reviews, paying rent, and just the outside external forces of COVID and policies. And so there's just for anybody running any business is challenging. So then you put layers on top of wanting to be intentional.

The lack of diversity and paying fair wages in the coffee industry

Historically, the most represented people in the coffee industry, on the roasting and cafe side, are white men. We want to hire a Black and African-American roaster since that does not happen often.

The talent pool is very small, so we've gone to adjacent industries, such as chocolate because you roast and develop, and wine because you have to develop your palate. We've trained people in adjacent industries to coffee, which takes more training. Every once in a while, you'll find one of those unicorns who are experts at what they do.

And now we've been doing this a long time, so they know us, and they're attracted. Sometimes, we can hire experienced people at the top of their game. Very often, we're training them and sourcing the talent to fulfill the promise that at the very beginning, I told you, we want to show up excellent, compete with the very best, and be very product-forward — we want to do that. But the challenge with this is paying a living wage and, ideally, paying more than minimum wage. When we started, we were paying $15 an hour, which today doesn't sound like much, but I think the minimum wage in 2014 in Oakland was close to $10-$11 an hour, and the federal minimum wage was $7.

We held at $15, but the minimum wage soon caught up to us. And then we had to try to stay, we went, we didn't just want to stay ahead to stay ahead. We wanted to be able to, but business is tough, and you can't just keep raising salaries. We're trying to make ends meet, and we're trying to get to that magical sort of break-even point when we're investing in elaborate industrial-scale manufacturing equipment. We want to compensate people fairly for their talent, work, and labor.

Operating in the Fruitvale District

Then, there are the struggles to show up and be on the corner in the hood. With sideshows happening, windows getting smashed, bullets flying, people that ain't well just wandering in and disturbing the peace.

Reevaluating partners

We also want to reevaluate our partners. For example, are our partners living up to our current expectations at the farm level? We validated it in 2017, but is it still valid in 2024? We don't have the budget to send people all over the world.

Standard HR challenges

When you hire folks who might not have gotten jobs at other places, some issues they come with are trust issues, antisocial behavior, and managing the HR side of people relations.

Getting past gatekeepers

Those are the handful of misconceptions about being a predominantly Black and Brown-owned company. The perception of big corporate clients means they'll throw a bone at us for Black History Month. Juneteenth showed up on the radar in the last few years, which is beautiful, and I don't resent it because we'll take that bone. We'll take the door's opening and prove what we can do to get our foot in the door. Now that the doors are unlocked, we will push our way in there. We'll meet with their Black employee resource group and have them advocate for us. We're going to get our foothold and try to build within there. But we're still going up against more established brands that may look like the purchasing managers' perception of quality.

Derrick: Thank you so much for giving me more context. I'm realizing how many pieces there are to all of this. But obviously, you're doing it with a wonderful team and community behind you.

I want to transition into what's happening in the Bay Area right now. There seems to be a national narrative about what's happening here and some of the stuff you see in the news when you tune in: "Oh, crime is like this in the Bay Area. Oh, it's not safe for tourists. Bippings and all these things are happening. Companies are moving out of Downtown SF and closing up business there." The narrative can seem troubling right now.

What advice do you have for local community-driven businesses as we continue to push forward and try to be a light in the Bay area and change that?

Keba:

Do what you need to do for yourself first

I would say do what's right for you and your family. I see people try to stick it out no matter what, and that's not necessarily always my advice. You could really get beat down. You could try sticking it out for the community because you love it. The reality is that many of us are stuck in a legal lease as a contract, or we're in debt, so it's not easy to quit. I don't want people to feel so obligated where it's just community first, and if this is just too much, too heavy, too much of a burden, and you need to tap out, do what you need to do for your mental health, your physical health, and your family. I don't want you out here having strokes, heart attacks, and mental anguish. It's no joke, but I understand what is at stake. People often put their life and family savings into these businesses and storefronts. And if you are in that position and you're going to stay in there and you're going to hang and stick it through, don't suffer silently. Tap in and let your community know.

What's interesting is there's a lot on this topic, but I'll hit some different points. Around here in Fruitvale, ain't nobody really getting bipped. But our business is down 30, almost 40% from last year. And it feels like it's the perception; it just feels like fewer people are out. There's just a fear. And it's not like shit doesn't go down in this neighborhood, but it's a different set of problems.

The general lawlessness is palpable in the streets. And I'm here a lot. I live five blocks up here. Then I come here to the HQ, and then five blocks, or three blocks the other way, is our real street. This is almost like my company campus. The Red Bay campus is right here in the Fruitvale District. So I'm here a lot. I always see sideshows in the middle of the intersection, so we have our challenges.

Let your community know what you need

One thing is we always want to make more posts. And I know a lot of entrepreneurs are proud people. We don't always want to get on social media and beg people to come to our shop or say, "Hey, we're struggling and need your support." We're proud people. I think about some advice I saw somebody give to musicians who have several thousand followers. They're complaining because they don't have millions of followers. But listen, you've got several thousand people in your room. These are your people. That's your tribe. Work with that, hold on to those people, and ensure they return. Tap in, voice what you need, and don't be shy about asking your community for what you need. You'd be surprised how they'll show up for you.

Build stronger relationships with your customers and community

Over the last week (at headquarters), I've been coming downstairs. There's a 4,000-square-foot location on the ground floor, with lounge seating, counter seating, and big windows. You could probably fit 40 people in here. There's a mezzanine looking over. My office is on the mezzanine. I'll go downstairs, pull up to everybody in the room, and tell them, "Thank you. It means a lot that you're here. I'm the owner of the company, and just seeing you here warms my heart as we're slower than we were last year. And you chose to come here today and sit here with a single cup of coffee for a couple of hours and take your calls, work on your paper, or just hang out. It means a lot, and don't think it's going unnoticed. And here's a free drink card for your next visit." I've been doing that, and it's touching. Like a woman yesterday was like, "Can I give you a hug?" And she just gave me a hug — I almost cried. And she was like, "I lived in his neighborhood, but somehow I just didn't get to coming here, and I thank you so much for having this kind of space." Another brother was like, "Oh man, I'm from Tennessee. I'm new to the area. I'm a teacher over here, but I got my side hustle. I make leather bags and love to collaborate on something." Another couple said, "Oh yeah, we were part of a downtown co-op restaurant, but we love coming here." These aren't just good gestures from me as the business owner. I get to learn about the people who show up. Another woman, an older Filipino woman, I wasn't sure if she even spoke English, but she had her cappuccino, and I could tell she understood what I was saying. And she was appreciative.

Anyway, back to the question of how we are dealing with this perception of Oakland and the Bay Area and trying to run a business during these times.

Advocating for small businesses

Some people are out there working behind the scenes on your behalf, on our behalf. People like Nigel Jones from Kingston 11 and Calabash. He should just focus on running his restaurant, marketing, getting people in the door, managing his staff, managing the food, just doing all the hard work it takes for a restaurant, sourcing the quality, and everything else. But he's out here at these community meetings, wrangling these city, county, and state officials holding their feet to the fire, demanding that they support the businesses.

Tap in with the business district communities. Every neighborhood has a little business community, our business association. You can attend community meetings or go to city hall and show up to support safer and cleaner streets; your local activists are out there pushing agendas, so please support them.

Engaging on social media

If you can't show up, post a picture because it goes a long way. Or if you can't post, like a comment. Often, social media is a lifeline because it's our primary channel for marketing, and it's what we can afford. We can't always pay to take out ads. So when you see your community business post something, don't just like it; comment on it, too. It shows engagement, which gets the algorithm going.

We have 45k followers, but we'll put a beautiful post out and get 80-100 likes, and I know this did not reach everyone. And I don't know about shadow bans and all that. But I do know that when we do one of these posts, we have a lot of engagement, like when we do say more overt political posts, like we did on King's Day, calling out the genocide in Palestine or in July with the fourth America calling out just the things that are happening in the country. And you have some people who might have different political opinions, and they're chiming in and challenging you. Our followers were trying to challenge them or clap back, but that level of engagement gets the virality going. So, of course, you first support the business with your dollars, let people know about it, and engage their social media in ways that help that message get out and reach the intended audience.

Derrick: Thank you so much for sharing your journey and the many vulnerable parts of the story. I feel much more connected to Red Bay now than before, and I'm very grateful for that. I appreciate this opportunity and your trust in me in this conversation and to tell your story.

Keba: Derrick, I appreciate you reaching out. You can imagine my email inbox moving so fast. I get hundreds of emails daily, and sorting through them is tough. Yours was pretty simple; you reached out, and something authentic rang through. I was like, "Alright, this is a real one. Come through, let's talk."

Since it's February, we've got some stories to tell, so let's tell them. We've been in this storytelling mode with the tenth anniversary, digging up all these stories. And when you hit ten years, going back to Guerrilla Cafe, I've been nostalgic and a little tender around the edges thinking about the folks that got us here and who we've lost. So, for sure, we appreciate it.

Adored this piece!!! Really makes me want to explore East Bay more :)